Placentophagy and Chinese Medicine

Originally published May 11, 2016

Disclaimer: The following blog is merely a collection of notes and not a serious scientific research paper. There is obviously a pressing need for more research. My intention with this blog post is not to make any conclusive statements about the practice of placenta encapsulation or placentophagy, which I am not qualified to do anyway, but merely to offer the classical Chinese perspective as an urgently-needed correction to some misinformation promoted in popular and Chinese medicine circles.

According to Wikipedia, “Placentophagy (from 'placenta' + Greek φαγειν, to eat; also referred to as placentophagia) is the act of mammals eating the placenta of their young after childbirth.” Based on an article by SM Young and DC Benyshek titled "In Search of Human Placentophagy: A Cross-Cultural Survey of Human Placenta Consumption, Disposal Practices, and Cultural Beliefs" (Ecol Food Nutr. 2010 Nov-Dec;49(6):467-84), Wikipedia also states that “Although the placenta is revered in many cultures, there is scarce evidence that any customarily eat the placenta after the newborn's birth.”

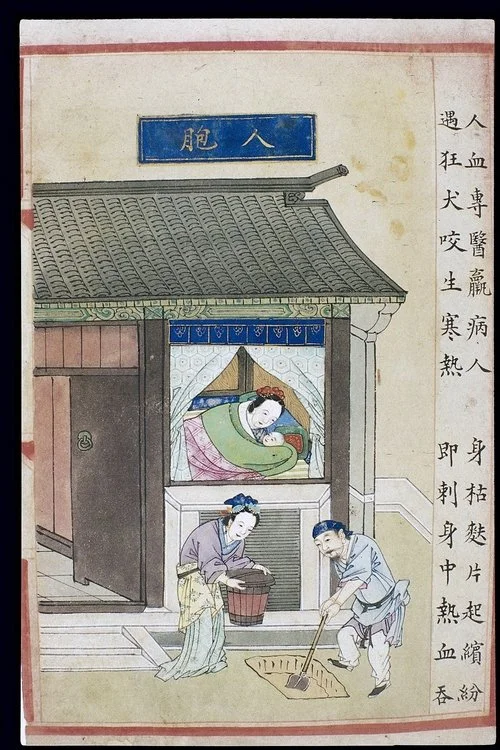

Chinese medicine practitioners involved in reproductive care often find themselves affected by a fairly recent but rapidly growing trend to encapsulate the woman’s placenta, sometimes with the addition of “traditional” Chinese herbs, and have the woman ingest these after delivery, presumably to treat postpartum exhaustion and depression and improve lactation. This issue comes up frequently when I lecture on postpartum care in classical Chinese medicine. According to one popular Chinese medicine lecturer on this topic who claims to be transmitting traditional Chinese medicine, “The Chinese have for centuries employed placenta… to prepare the placenta for consumption by the mother and to correct and augment post-parturition mothers with insufficient lactation.” Under a series of slides all titled “Traditional Chinese Medicine Method,” this person offers a recipe as “popularized by Raven Lang” but in the next bullet as “the oldest-known and most commonly-used recipe for postpartum placenta preparation,” with no reference cited for this statement.

As a critical historian who has spent literally decades immersing myself in the classical gynecological literature from China, with a special interest in postpartum recovery and a painfully long Master’s Thesis written on the topic of Placenta Burial in Early China, statements like these concern me greatly. I see well-meaning but gullible practitioners accepting them without challenge and promoting the practice to their equally gullible patients. I have, however, never come across a classical Chinese source that recommends having women eat their own placentas (or any placentas, for that matter) in a course of treatment for postpartum recovery. Placentophagy (eating one’s own placenta) is a rapidly growing practice promoted by non-biomedical healthcare providers worldwide, especially in the United States, and may well have its uses. However, it is NOT a traditional Chinese medical practice and must not be promoted as such to unsuspecting patients who trust us to care for them safely and confidently with treatments that have undergone the critical tests and experiences of many centuries and thousands of highly educated professional physicians.

Before addressing the records on the medical use of placenta in Chinese pharmaceutical and materia medica literature, let me give some cultural context for information on Chinese attitudes toward the placenta that we do find in the written record.

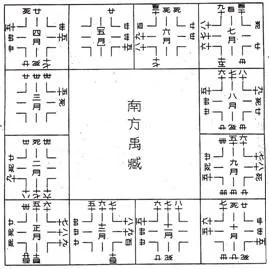

The connection between the placenta and the child that was wrapped in it during its time in the mother’s womb is a theme of great importance in early Chinese medico-religious literature. In fact, placentas are regularly mentioned with a very different intention than their consumption as medicine, namely in the context of placenta burial charts and instructions on how to safely dispose of them by burial, to avoid harm to both the mother and the baby by offending all-powerful spirits. I should know because I wrote my Master’s Thesis on this topic. The chart to the right is a reproduction of an illustration from the Mawangdui tomb that was closed in 168 BCE, which is explained in the accompanying text: According to the instructions given there, the placenta must be washed and rinsed carefully, placed in an earthen container that is carefully sealed to prevent anything from getting in or leaking out, and buried in a “yáng” location, where the ground is dry and exposed to sunlight, to ensure intelligence, health, and a good complexion in the baby. The twelve squares on the outside ring of the chart represent the twelve months. Each month’s square contains twelve further positions with the directions that are either auspicious or inauspicious for that month, or even cause death when they coincide with the positions of the Big Dipper and Jupiter, presumably by offending their ruling astral deities. Like the entire process of childbirth and all its byproducts, it was essential to ritually and physically contain the placenta and avoid exposing it to outside spirits who would be offended and could then cause harm if not death to the child and/or mother.

Placenta as a medical substance is not mentioned in the early classics like the Divine Farmer’s Classic of Materia Medica 《神農本草經》 (recently translated and published by me and for sale here) or Sun Simiao’s 孫思邈 Essential Formulas Worth a Thousand in Gold to Prepare for Emergencies 《備急千金要方》, or in any other classical gynecological treatises on postpartum recovery that I remember. Without having time to do an exhaustive literature search right now for the earliest occurrence of placenta in materia medica literature, it is most definitely not ever a substance that was given to women as part of standard postpartum recovery.

What the later materia medica literature does agree on is that placenta as a human medicinal is a very powerful substance that should not be used lightly, was fraught with danger, and was definitely not indicated for everybody or everyday consumption. Given its efficacy and potency, it is only obvious that it had just as much potential to do harm as to do good.

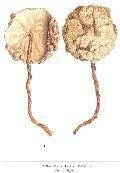

I have never seen any evidence at all in historical sources of women consuming their own placenta. In other words, placenta was a rare medical ingredient that was collected, prepared, and sold by a few elite pharmacists to strangers with no connection to the original human source. In all texts, it is emphasized that the placenta must be collected right after birth and must come from a strong healthy mother free from disease. Especially the exposure to “fetal toxin” 胎毒 in the mother’s womb will render this substance harmful!

Placenta is a rare medicinal used for extreme cases of deficiency, emaciation, insanity, etc. As my translation below will show, it is also mentioned in passing as useful to women suffering from infertility, menstrual disorders, extreme emaciation, and lack of breastmilk. Translated into a contemporary context, these are exactly the women who end up taking all sorts of fertility drugs because they are too weak and depleted to secure and maintain a pregnancy naturally. As a result, their placentas are by definition inappropriate for human consumption, especially when we consider the toxic residues of these medications that are bound to remain in their placentas, which might then further get passed on through the baby through breastfeeding!

What follows below are just a couple of examples from major materia medica texts. There may be earlier records of placenta use in Chinese medical literature but I have not come across any at this point.

Li Shizhen's 李時珍 famous Compendium of Materia Medica 《本草綱目》, which was first published in 1593, does list placenta, under the medicinal name “purple river vehicle” 紫河車 , but not in the context of postpartum recovery and not as a substance that should be consumed by the mother herself. Here is my translation of the entry:

During the fetal stage of the child, the umbilicus is tied to the mother, and the fetus is tied to the mother's spine and receives the mother's yin. It is formed from the blending of the father's essence with the mother's blood. Even though it is a later-heaven (post-natal) substance, it truly has received the earlier-heaven (pre-natal) qi and clearly is incomparable to any other substance in the categories of metals, stones, herbs, and trees. Its enriching and supplementing effect is extreme. Consumed alchemically over a long time, it sharpens the ears and eyes, makes the hair on the head and temples pitch black, extends the years, and boosts longevity.

兒孕胎中,臍系於母,胎系母脊,受母之蔭,父精母血,相合而成。雖后天之形,實得先天之氣,顯然非他金石草木之類所比。其滋補之功極重,久服耳聰目明,鬚發烏黑,延年益壽”

Before we jump to conclusion on its popularity, it behooves us to consider the nature of this source, which contains information on a broad array of natural substances and their effects on humans from the perspective of natural science, as opposed to medicine per se. It is a great collection of stories, oddities, marvels, etc, which Dr. Carla Nappi, a medical historian and author of a fantastic book on this text called TheMonkey and the Inkpot has described as a "cabinet of curiosities.” As such, the text also describes humans who are pregnant for several years or spontaneously changing sex, with multiple heads and tails, human-animal combinations hanging from trees by their tails, a beast with monkey or pig-like hair and ears but human face, corpse eaters, man-bears, wild women, earth-sprouting lambs whose umbilicus is connected to the earth but who can break this connection to run away like a regular lamb, dragons and phoenixes, and plenty of demons. All of these are described in great detail, with reference to their medicinal properties.

The Essentials on Materia Medica 本草備要, a more narrowly medical work by Wang Ang 汪昂 from 1694, does contain an entry on placenta where it describes it tersely as “greatly supplementing qi and blood, sweet and salty, and warm.” It lists it as indicated for all extremes of deficiency taxation (damage to the lung, heart, spleen, liver, and kidney), and for mental confusion and insanity. It emphasizes that good placenta must be processed right after birth and must come from a woman with perfect health, warning that placenta that contains “fetal poison” 胎毒 is harmful. It is prepared by rinsing it clean and then simmering it in liquor, drying it, and grinding it into a powder. The second half of the entry quotes the effect on the child when the placenta is disposed of incorrectly: It causes insanity in the child when eaten by pigs or dogs, sores and lichen when eaten by mole crickets and ants, miserable death if eaten by birds, rotting sores when consumed by fire, and so on. The entry concludes with a stern warning that even though some people claim that human [medicine] is able to supplement human [patients], this substance should really not be entered into the medical record!

To take this discussion into more contemporary waters, some information on placenta can be found in my 1981 edition of the massive four-volume Great Dictionary of Chinese Medicinals 《中藥大辭典》, which contains almost 6000 medicinal substances and is arguably the most comprehensive and authoritative listing of Chinese medicinals available today. Placenta is described there briefly as sweet and salty in flavor, as warm or greatly warm in thermal quality, and as entering the liver, lung, and kidney channels. Its effects are summarized as supplementing blood, nurturing qi, and boosting essence. As such, it treats generalized deficiency, emaciation, taxation heat, bone steaming, panting, coughing blood, night sweating, seminal emissions, erectile dysfunctions, and women’s insufficiency of qi and blood, infertility, and lack of breastmilk.

Without the time for a serious research paper at the moment, let me also cite a brief article on “The Use of Placenta to Assist Deficient and Weak Patients by Supplementing the Body,” which was published on August 25, 2014 in Hong Kong’s second best selling newspaper Apple Daily News 蘋果日報. Reflecting perhaps the growing popularity of placentophagy around the world, this admittedly non-academic article cites two medical experts: First, Dr. Kwan Chi-Yee 關之義, president of Hong Kong's Chinese Medicine Association and of the Chinese Herbalists Association, emphasizes that contemporary Chinese pharmacies do not sell human placentas but those from pigs or from sheep or goats. He mentions the traditional use of human placenta for male and female patients with physical deficiency and weakness to strengthen their health and to recover physiological functions. While he also, many years ago, once met somebody who had consumed human placenta in the interior of China (i.e., what we'd refer to as the “boonies” in the US), he expresses serious concerns about placenta being given as a treatment for postpartum depression and warns that it will actually worsen the health in certain patients. Next, the article cites the renowned obstetrician and gynecologist Kun Ka Yan, who offers the concluding statement of the article that the value of ingesting placenta for medical purposes is suspect and not worthwhile.

To conclude this blog, placenta is clearly a medically powerful substance that must not be taken lightly or indiscriminately, for the sake of both the mother and the baby who will absorb whatever the mother ingests through the breastmilk. This is particularly relevant in our modern age when many women’s placentas are bound to contain residues from environmental and dietary toxins, not to mention the fertility drugs that are becoming more and more pervasive as natural fertility continues to decline. Regardless of the applicability of this information in our contemporary world, it is clear that placentas were handled with great care throughout Chinese history and recognized to be powerful substances with the potential to do harm to not only the child but also to the mother when not disposed of properly. Again, there is no evidence in Chinese literature at all of women consuming their own placentas and of women consuming placenta as a standard treatment for postpartum recovery. As Sun Simiao warned us in his authoritative writings on women’s health especially in the context of postpartum recovery,

In all cases, it is not only during delivery that women must worry. When they arrive at the postpartum stage, they must exercise particular caution. This is where the greatest threat to their lives is found.

Do not leave them without company at the time of delivery. Otherwise they might act without restraint and follow their whims, in which case they are bound to violate the prohibitions. At the time of the violation, it might be as tiny as autumn down. But the contracted illness will be larger than Mount Song or Dai.

Why?... After women have completed delivery, their five organs suffer from vacuity emaciation. You may only use supporting and supplementing treatments and must not use transforming and draining treatments.

In cases of illness, you must not prepare “galloping medicines.” If you employ galloping medicines, [the illness] will shift into one of even greater vacuity, resulting in her center becoming even more vacuous. You are thus distancing her from the path towards life.

The practice by some contemporary Chinese medicine practitioners to recommend placenta encapsulation to postpartum women as a standard traditional Chinese medicine treatment for postpartum recovery directly contradicts the message from the classical texts. Not only is there no historical precedent for this practice, but the classics are very clear on the dangers of giving the wrong treatment to women during this extremely vulnerable stage in their life! Whether you promote placenta encapsulation or not is your own choice, but please do not connect it in any way with so-called “traditional Chinese medicine.” On the other hand, the classics offer literally thousands of medicinal formulas and other treatments and advice for postpartum recovery that have been tested for safety over thousands of years by thousands of educated physicians. As practitioners of Chinese medicine, we do have access to this information and are qualified to make use of it. So rather than giving women pills to alleviate postpartum symptoms in a culture that simply does not sufficiently care for women postpartum, become active and engaged in this important area of classical Chinese medical practice!