Nurturing the Small

Pediatrics in Chinese Medicine

Yang Xiao 養小: Quotes by Sun Simiao on Pediatrics

The information posted below only skims the very surface of this important topic. If you want to learn more about classical Chinese pediatrics, check out my books Venerating the Root, Part One and Part Two.

The Significance of Pediatics

(excerpts from the introduction to Venerating the Root)

Based on extant medical writings from antiquity in both China and Europe, the proper care of newborns and young children was a topic that received far greater attention in early and medieval China than in Europe. To cite just one example, the Yiwenzhi 《藝文志》, a bibliographic treatise from the first century CE that details the holdings of the imperial library in the early Han period already lists a full nineteen volumes of formulas for women and children. By contrast, we find only short comments on individual diseases in Western medical literature by famous authors like Soranus of Ephesus (ca. 100 CE), Galen (ca. 200 CE), or Avicenna (ca. 990 CE), but no separate book-length treatises until Hieronymus published the first book on children’s diseases in 1583. In the following centuries, writings on pediatrics became more common but there is no doubt that compared to other medical fields pediatrics is a very young specialty in the history of Western medicine. One could even argue that this attitude is still reflected in the lack of attention paid to pediatrics in modern TCM education in Western countries, especially when compared to Chinese medicine as practiced historically in China. It may therefore surprise even experienced practitioners of Chinese medicine who are unable to access the Chinese primary sources on their own, to learn of the emphasis placed on the care of women and children in the traditional Chinese medical literature.

The text that provides the source for the translation in the present book is a monumental encyclopedia of medicine called Beiji Qianjin Yaofang 《備急千金要方》 (Essential Formulas Worth a Thousand in Gold to Prepare for Emergencies) that was completed by Sun Simiao in 652 CE, in the early Tang dynasty. While certainly a pathbreaking work in the history of Chinese pediatrics, its diagnostic and therapeutic advice did not appear out of nowhere but was firmly rooted in earlier texts, most of which have unfortunately not survived the vicissitudes of time. And the principles and treatments mentioned here were quickly expanded on and deepened in the following centuries, resulting in a whole body of literature on pediatrics when the field was established as a full-fledged medical specialization in the Imperial Bureau of Medicine during the Song dynasty…

The placement of the information on children right after the section on gynecology but ahead of the main part of the book that covers general medicine is highly significant. As Sun Simiao himself stated unequivocally, this radical innovation and restructuring of medical information was not coincidental but on purpose. In his own words, he prioritized the health and welfare of women and children over those of other family members in order to “venerate the root.”

Of all of Sun Simiao’s medical innovations, such as the introduction of Indian drugs and treatment methods, the first mention of the a-shi point 阿是穴, the protocol of the so-called “thirteen ghost points” 十三鬼穴 , or his essay on medical ethics, his most important contribution to the history of Chinese medicine may well be this emphasis on gynecology and pediatrics as areas of special concern for any medically-oriented “specialist of nurturing life” 養生之家. The effects of this attitude can be seen to this day in the continuing significance of gynecology and pediatrics in Chinese medicine as practiced in contemporary China. Because of a lack of translations, however, this is an emphasis that has unfortunately not been recognized and utilized to its fullest potential in the application of Chinese medicine in non-Asian environments. It is my hope that the publication of this translation may serve as the beginning of a greater recognition of the potential role that traditional Chinese pediatrics can play in providing the best possible care for our children today. By making this ancient text accessible in English, I hope that practitioners worldwide will feel empowered and inspired to explore a field of Chinese medicine that is woefully neglected and underutilized at the moment by most practitioners of Chinese medicine in a non-Asian context…

Nevertheless, the extent of Sun Simiao’s emphasis on the care of women and children over any other aspect of medicine suggests that his interest was peeked by more than just the political value and cosmological significance of promoting the feminine, yin, or the giver of life in the case of women, and the small, vulnerable, stage of inception, birth, at its most yang stage, in the case of newborn children. For a more complete answer, let us look at Sun Simiao’s actual writings. There is no doubt that the Qianjinfang is a central text in the history of Chinese medicine. A gigantic encyclopedia, its thirty volumes contain over five thousand entries in the form of 方 fang (“formulas,” “recipes,” or “prescriptions” in the largest sense of that word, but literally meaning “directions”) and occasional short essays. These fang cover a large range of therapeutic approaches, representative of all that was considered medicine 醫 in medieval China: internal medications (medicinal decoctions, powders, pills, pastes, jellies, or liquors), external treatments (ointments, plasters, hot compresses and suppositories, fumigations, baths, beauty treatments, physical manipulations, and acupuncture and moxibustion), religious methods (talismans, exorcistic rituals, spells, and incantations) and what we might call lifestyle advice (exercise, diet, sexual intercourse, avoidance of stress and overwork, etc.).

Even a cursory look at the outline of the Qianjinfang reveals that Sun Simiao organized his information in a way that differs dramatically from contemporaneous medical texts: The famous formula collection Jingui Yaolüe 《金匱要略》 (“Essential Prescriptions of the Golden Cabinet,” Eastern Han period) covers women’s conditions at the very end of the general section, followed only by a brief section on “miscellaneous formulas” and dietetics that most scholars believe to have been added to the original text in the Song period, and has nothing at all to say about pediatrics. Another text, composed only decades before the Qianjinfang but clearly influential for Sun Simiao’s thinking, the Zhubing Yuanhoulun 《諸病源候論》 (“On the Origins and Signs of the Various Diseases,” 610) covers pediatrics in the very end, following right after the information on gynecology in the last six of fifty volumes. What is significant in this context, however, is not that pediatrics is placed at the very end of the text but that over a tenth of the total text is devoted to this topic. Its author, Chao Yuanfang, served as officially-appointed imperial physician and erudite in the Sui dynasty court. Following a similar structure and weight, the Waitai Miyao 《外臺祕要》 (“Classified Secrets From the Palace Library,” 752), another formula collection that was published slightly later than the Qianjinfang, covers the prevention and treatment of pediatric diseases in volumes 35 and 36 out of 40, right after volumes 33-34 on gynecology, recording about 400 formulas in 86 chapters. We can therefore presume that pediatrics was a topic near and dear to the heart of not just Sun Simiao as an individual but of medically-inclined writers and practitioners during the early Tang period in general.

The important role pediatrics played in medieval Chinese medicine is further confirmed a few centuries later by its official recognition in terms of publications and institutional structures in the imperial medical bureau of the Song dynasty. This initial stage of pediatrics culminated in 1119 with the publication of the Xiaoer Yaozheng Zhijue 《小兒藥証直訣》 ("Straight Tricks on Medicinals and Signs in Pediatrics") in three volumes, composed by the famous pediatrician Qian Yi 錢乙 after more than 40 years of gathering clinical experience and academic research. The first volume, titled “Pulses, Signs, and Treatment Methods,” discusses information on physiology, pathology, five-zang organ-based disease differentiation, and 80 disease patterns. Volume two, titled “Case Histories,” presents Qian Yi’s personal clinical experience in 23 case histories; volume three, on “Various Formulas,” contains essential pediatric formulas and introduces 122 of Qian Yi’s own most effective formulas. As the preface to his book states (my paraphrase), medicine is already a difficult art, but pediatrics is particularly difficult for the following reasons: First, not much information is recorded in the classics. Second, children’s pulses are difficult to read and small children (here defined as below the age of seven) easily wail from fright, forcing the physician to rely on outside signs. Third, their bones, qi, body shape, and voice are not yet fully developed and they often behave abnormally, whether crying in sadness or laughing in joy. Small children cannot speak yet or their words are unreliable, so it is impossible to gain information by questioning them. Children’s internal organs are weak and thus susceptible to vacuity or repletion or heat or cold. In addition, ordinary physicians carelessly prescribe substances like xijiao (rhinoceros horn), zhenzhu (pearl), longgu, and shexiang, complicating the condition. For this reason, ordinary physician kill four out of ten patients by mistreatment…

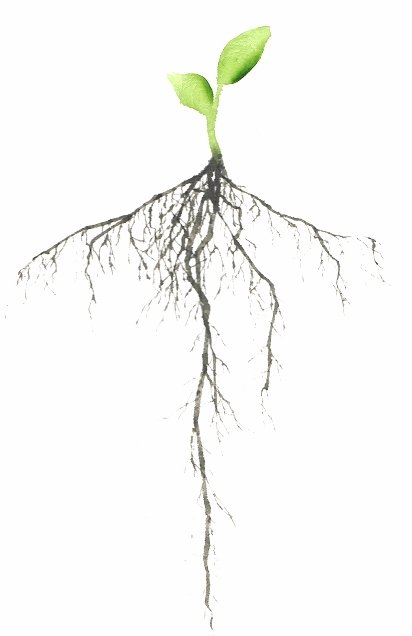

How did this way of thinking, these views on medicine, ethics, and self-cultivation, affect Sun Simiao’s attitude towards pediatrics? The most logical explanation in my mind, though never spelled out by Sun Simiao or his contemporaries, hinges on the meaning of the term yangsheng 養生, referenced consistently throughout the Qianjinfang. Usually translated literally and quite adequately as “nurturing life,” the etymology of the two separate characters that make up the term might shed some light on what the early Chinese had in mind when they used the term. The character 生 sheng is fairly straight-forward: It is an image of a plant emerging from the ground, a sprout in the early stage of growth. Hence it means “life,” “birth,” “generation” in addition to its narrowest meaning of “sprouting.” As such, it is used twice, for example, in a classic line from Suwen 《素問》 5, first to refer to the first of the four stages of development in nature throughout the four seasons and second to the verb “produce” or “engender”:

天有四時五行,以生長收藏,以生寒暑燥濕風。

“Heaven has four seasons and five movements, whereby it causes birth, growth, gathering, and storing, and whereby it engenders cold, summer-heat, dryness, dampness, and wind.”

We can see how in both contexts the metaphor of “sprouting” fits quite well. The first character in the compound yang sheng is perhaps even more evocative: 養 yang is a combination of 羊, the image of a sheep or goat, the quintessential sacrificial animal, hence here conveying the notion of sacrifice to the spirits or one’s ancestors, and 食, a character denoting “food” or “feeding.” As a combination of these two components, the character 養 hence referred originally to the concept of offering food in sacrifice to one’s ancestral spirits. From there, it came to mean “nourishing,” “nurturing,” “supporting,” “cultivating,” or even “rearing” in the context of animal husbandry. On the most general level, perhaps “providing for” or “offering sustenance” are good renditions.

So how might we use the concept of yang sheng to explain Sun Simiao’s unusual emphasis on the care of women and children and radical break with literary tradition? As he himself stated, after all:

“The diseases of small children are no different from those of adults. The only difference lies in the quantity of medicinals that are used. The eight or nine chapters on fright seizures, intrusive upset, separated skull, failure to walk, etc. are here combined into the present volume. Other treatments for conditions like diarrhea etc. are scattered throughout the various other volumes and can be found there.”

Viewed at from this angle, it surely would make more sense to follow tradition and explain the care of the human body in general, regardless of gender or age differences, first, before delving into specialized conditions. Nevertheless, as soon as we translate the term yang sheng literally as “providing for sprouting,” and recall the centrality of this notion in Sun Simiao’s life and work, the answer is clear. I therefore propose that Sun Simiao consciously broke with literary tradition and placed the formulas for women and children in front of the general section to emphasize the importance of “venerating the root,” of truly and literally supporting the process of life in its entirety by beginning with generation and sprouting. The extent of Sun Simiao’s clinical experience may always remain a mystery, at least to critical historians like myself, but the more I study Master Sun’s writings, the more that question becomes a mute point. More important to me is Sun Simiao’s very real and explicit sensitivity to the fragility of life at its inception, yet another expression of his sagely insights into the transformations of qi in the natural cycles of life, in the macrocosm of heaven and earth as much as in the microcosm of the human body…

Motivated by this recognition of the importance of “nurturing the small,” Sun Simiao then proceeded to provide all the relevant information he was able to find on the proper care of neonates, infants and young children. The information in these pages strikes a useful balance between his repeatedly stated preference for “treating disease before it arises” (治未病 zhi wei bing) and his desire to address the real practical needs of his readers to “prepare for critical situations” (備急 bei ji), as the full title of the his book proclaims, or in other words, between preventative care and the treatment of urgent existing disease…

(Below see Sunjae Lee's gorgeous painting, commissioned for the cover of Venerating the Root.)