A Lactation Consultant’s Perspective on Placentophagy

First published on September 6, 2017

A photo by Meghan Joy Yancy of her fourth baby. See www.meghanjoyyancy.com for her blog.

The following is a guest post by Sarah Hollister RN, PHN, IBCLC. Sarah contacted me a few weeks ago after coming across my own blog post on maternal placentophagy while doing research on the Chinese medicine roots of this practice. We both are excited to collaborate and share her experiences and research here since we believe that it is important to approach this sensitive subject with as much solid information as possible. It is my hope that the Chinese medicine community might benefit from Sarah's extensive experience as a nurse and lactation consultant. For references cited and used in the following article, see this handout in pdf format, which Sarah shares with clients and colleagues. We both welcome your comments, feedback, and constructive criticism of our contributions to this evolving discussion. Please feel free to share our writings with your patients, colleagues, family, and friends.

As a nurse and an International Board Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC), I have the opportunity to work with nearly every pregnant woman and new mom and baby at a group of four primary care health centers in Northern California. I would like to share my experience, concerns and request for collaboration to closely examine the new practice of placenta encapsulation, as it has grown to become a component of the postpartum experience for the new moms who I work with and throughout the United States. I have encountered assumptions that placenta consumption increases milk production, is a prevention for postpartum depression, and has existed in history as an ancient human practice. I will provide a summary here of the work I do and what I have found with my clients involving this practice.

In my role providing perinatal services, I work both within the community clinics offering prenatal education, and in the mom’s home doing the initial exams for the newborns and breastfeeding assessments for moms after every birth as the standard of care, whether things are going well with breastfeeding or not. When there are challenges with breastfeeding, I am able to offer unlimited lactation consultations. All of my services are free of charge to the moms, as they are provided through our clinics’ primary care services. I also hold a weekly drop-in lactation clinic and postpartum support group. In addition, I have one-on-one assessments scheduled with all moms at four weeks postpartum as a routine visit. My visit notes are immediately available to their primary care physicians. I have access to the babies’ growth charts as well. I work closely with the family practice doctors, who are very supportive of breastfeeding and are trained to do interventions for breastfeeding challenges such as frenotomies for tongue-ties and osteopathic craniosacral therapy to help with latching issues related to the birth. With all of this, I have full access to our community of moms and babies over the long term of their care, and great resources to support breastfeeding success. Our patient population is quite varied, with women giving birth in hospitals, birth centers, and at home.

Over the past five years, I have noticed an alarming trend of moms with low milk supply and failure-to-thrive babies. It was initially a puzzle to me, as the majority of these cases were with healthy moms who had given birth at home or at a birth center, or at least had a doula supporting them in the hospital, all factors that should set a mom up for an optimal start to breastfeeding. They usually had no explainable reason why their milk supply was so low, as I worked diligently with them on resolving any factors that could be contributing. It was another lactation consultant who was consulting with me on one of these cases who brought up the fact that the mom was consuming her encapsulated placenta. I had assumed that this was a healthy and even traditional practice of which I was supportive, and brushed it off as having nothing to do with her low milk supply. However, in discussing it more deeply, and looking into the physiological connection between pregnancy hormones and lactation hormones, my colleague’s concern began to make sense to me. We know very well that the dominant pregnancy hormone, progesterone, inhibits the dominant lactation hormone, prolactin, from binding to the prolactin receptor sites, thereby inhibiting milk production during pregnancy. A woman’s milk comes in at approximately three days after the birth because of the rapid drop in progesterone due to the expulsion of the placenta from the body. This is the hormonal trigger that allows prolactin levels to rise and milk production to begin. If there are retained placental fragments in the uterus after the birth, a woman’s milk is likely to be delayed coming in because of the inhibitory effect of the progesterone on prolactin, thereby halting Lactogenesis II (i.e., the onset of copious milk production on day 3 after the birth). Estrogen is the other dominant hormone of pregnancy, and it is also a potent suppressor of prolactin during lactation. When a nursing mom gets pregnant with a new baby, her milk is at risk of drying up due to the hormones of the new placenta growing. We know of the detrimental effects hormonal birth control can have on milk supply. This is a very basic fact of lactation physiology: progesterone and estrogen are inhibitors of prolactin (Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine, Protocol #13, 2015; Neville et al., 2001; Riordin, 2005; Walker 2017).

I went back to the previous cases I had encountered of moms who never established a full milk supply or whose babies took 4-6 weeks to regain their birthweight despite immediate and extensive lactation support, and interviewed them about this piece of information. I found that nearly all had consumed their encapsulated placenta. I started paying attention to this possible correlation, and asking all the new moms I worked with whether they were consuming their placenta. Over the past four years that I have been aware of this issue, I have noted many cases with a clear negative effect of placenta pill consumption on milk supply. I find that the sooner a woman stops taking her placenta capsules, the sooner her milk supply will begin to increase. However, if I don’t find out about this fact until after she has consumed the entire 4-6 week course of them, the milk supply often cannot be fully established. Based on my personal experience, placenta pills are likely to suppress a woman’s milk supply by approximately 50%. In addition, I have been hearing increasing reports from other lactation consultants, both locally and nationally, that confirm these same findings of low milk supply associated with placenta consumption.

I now discuss this information with all women who I see in their pregnancy, and advise them against consuming their placenta. I point out to them that there are no valid research studies that prove that placenta consumption either improves or suppresses lactation, but that risking milk supply is not a decision to be taken lightly and that my colleagues and I are seeing a concerning trend. I share with them the recent research papers on this topic, including literature reviews that show that postpartum placenta consumption is actually a new trend and has not been a human tradition found in any culture (Young et al.,2010; Cole, 2014; Coyle et al., 2015; and Hayes et al., 2016).

Artwork originally by Mara Berendt Friedman, cited as placenta burial art in Nurturing Our Wildness

I show them a recent study that offers data on the hormonal content retained in placenta pills after the processing and encapsulation (Young et al., 2016). The authors of this study found that there are only estrogens and progesterone remaining in the pills and that these reach physiological effect thresholds. This fact helps us understand the hormonal picture we are seeing with the suppression of milk supply. Another recent study shows that there is no iron benefit to consuming placenta vs a placebo, which debunks one of the claimed benefits of consuming placenta that is promoted by encapsulators (Gryder et al., 2016). The doctors at our clinics are giving the same message to all pregnant women to not consume their placenta, based on these cases we have seen. With this prenatal education, the cases I now see of low milk supply have markedly decreased. I still get women coming into my lactation clinic who are new to our health center, referred to me for low milk supply and failure-to-thrive babies and again, placenta encapsulation is the most common reason that I find for this problem.

I had my own two babies with midwives, the first at a Birth Center and the second as a home birth. I have experience both personally and professionally with the high quality of midwifery care, and I remain very supportive of the traditional work that midwives and doulas do. A large percentage of my clients give birth with our local midwives and doulas, so I have many opportunities to share the care with them postpartum. Yet I have encountered resistance from some doulas and midwives upon hearing my concerns about placenta encapsulation. The response I often get is that placenta pills are “medicine” for postpartum depression and boost milk supply, and that they have never seen women who had negative experiences. Yet, these moms who I have worked with and whose problems I have documented are often also the clients of those midwives and doulas. As such, I am concerned that the doulas and midwives are in fact not accurately assessing milk supply and infant weight gain and therefore do not see the picture I am seeing. In a normal situation, as long as the latch is comfortable, mom is nursing following baby’s cues, and you can hear swallowing, it is generally assumed that all is well with breastfeeding and that mom has plenty of milk. Nevertheless, infant weight gain is the most reliable indicator of milk supply, and weight checks at key points in the early days and weeks help to monitor for adequate growth and to identify red flags.

Marsden baby scale

Often the baby’s slow weight gain goes unnoticed using the common “fish scale” that midwives use in their practice. The fish scale is easy to transport to the home and cradles the baby in a comfortable sling-like hold but measures in two- to four-ounce increments versus a digital scale that is calibrated to measure newborns in grams. Digital scales are much more accurate in assessing daily weight gain as well as breastmilk intake per feeding. Cases of low supply and slow weight gain can be too subtle and nearly impossible to detect with the fish scale, which may otherwise be adequate for its purposes in a normal breastfeeding situation. When I detect slow weight gain, sometimes the response from the midwives or doulas is that the mom has plenty of milk and that the baby is just following his or her own weight gain pattern. Babies have been brought into the clinic for the first time still significantly below birth weight by two or even four weeks of age, or are still gaining weight far below the expected range by the two-month visit. Such cases of failure to thrive are sometimes diagnosed in the clinic by looking at the growth curve in the baby’s growth chart, following the completion of the six-week midwifery care, so in many cases the midwife is not ever made aware of this finding. In so many of these low supply cases, the moms themselves report that they believed they had full milk supply. They commonly say that they believed breastfeeding had been going very well because baby nursed with a pain-free latch “every 45 minutes to an hour around the clock.” When nursing a baby, this is actually often a sign that there is not enough milk, not a sign that there is plenty. I am concerned that the assessment and reporting of milk supply remains a complex issue. As a lactation consultant, I have seen enough direct cases that I have serious concerns about the increasingly popular practice of having postpartum women consume their encapsulated placentas.

The claim made by placenta encapsulators that these pills will increase milk production is certainly not based on valid current research, nor does it make physiological sense. With that said, I have spoken with several moms who have told me that they had previously consumed their placenta and never had milk supply issues, and I have been able to verify that their babies had gained weight normally. I am sure this is a part of the picture as well, as we also know that some women’s milk supply can withstand hormonal suppression from birth control pills while others don’t. In any case, this remains a high-stakes gamble.

In my postpartum support group, I have seen women struggle with profound postpartum depression after taking their encapsulated placenta, especially as they are dealing with such heartbreaking milk supply issues. Tragically, most of these women had decided to take their placenta pills primarily to prevent postpartum depression. I wonder about the reasoning behind this idea. Is this accurate or even ethical to tell women? Isn’t your body meant to flush out the pregnancy hormones after the birth to allow the lactation hormones to come in? This is the big hormonal shift during the ‘baby blues’ that is happening with the natural hormonal cycling, and by clinical definition is not postpartum depression. I am concerned that the popularization of the “Happy Pill,” as many encapsulators refer to it, is not only potentially risky but is giving women the message that their body is naturally set up for depression and that they need a hormonal pill to “prevent” this process. What happened to the advice for women to trust their bodies? What is a “balanced hormonal state” for a lactating woman? I am concerned that there is a lack of understanding among some healthcare providers about the hormonal cycling from pregnancy to lactation. Continuing to give yourself pregnancy hormones for days and weeks and months once you’re done being pregnant doesn’t sound to me like a balanced hormonal state. I can appreciate the likelihood that ingesting estrogen and progesterone, which are steroid hormones, could certainly cause the dramatic energy surge moms so often report after consuming their placenta, but who can be certain that this is a natural and healthy state for postpartum women?

As the popularity of placenta encapsulation grows, we are seeing new situations and new potential risks that deserve a closer look. Ingesting the placental estrogens may increase a woman’s risk for thromboembolism (blood clots, stroke) as we know estrogen-containing birth control pills can (Hayes, 2016; Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine, Protocol #13, 2015). In yet another new development, many moms are now even advised by encapsulators to give their infants and toddlers the placenta in powder or tincture form as medicine for colic or temper tantrums. What are the health implications for babies ingesting these hormones? The GBS Case Report that the CDC released this year on an infant hospitalized from an infection coming from the same strain of GBS found in the mom’s placenta pills (Buser et al., 2017) illustrates that infection is yet another potential risk associated with this practice.

Given the recent valid research studies that clarify that no human culture ever had postpartum women routinely consume their placenta begs the question whether humans have evolved to not eat their placenta for a good reason? We can continue to experiment on our new moms and babies and find out, but I believe this raises an ethical dilemma.

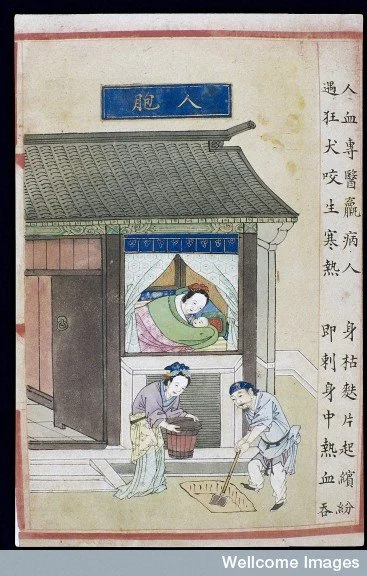

Painting taken from the supplement to Buyi Lei Gong’s Guide to the Preparation of Drugs (1591 edition), from Wellcome Images.

Lastly, my concerns about this fad of placenta encapsulation becoming the ‘new normal’ for postpartum care are not just for the implications to the moms and babies. My concern is also for the future and legacy of ancient wisdom in women’s health care. Midwifery is based on a long history of trusting a woman’s body and a tradition of providing safe, natural, and effective care. Aside from a brief exploration in the US in the 1970s of consuming whole cooked placenta, extensive research into world cultures shows us that it has clearly not historically been a part of standard midwifery practice to give women their placenta to eat. The covert social marketing that certain entrepreneurs have developed has in essence hijacked the knowledge and role of midwives and integrated a new practice into women’s health care. I see a similar disservice being done to Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). TCM is a highly complex system of medicine that has developed over thousands of years. Placenta encapsulation “specialists” are being trained online by business people, and after only watching a two-hour training video are told they will have “acquired experience in Traditional Chinese Medicine and placenta encapsulation.” Consequently, they are prescribing placenta pills under the name of TCM. Is there information included in the training that placenta consumption is actually in opposition to the medicinal properties indicated for postpartum women in TCM and that its use for postpartum care is actually not found in any of the traditional Chinese medicine texts? Will we allow a two-thousand-year-old system of medicine to get derailed this easily? There is much at stake in this new era of social media and cottage industries. Unfortunately, women’s bodies are the playing field.

I have made a handout that I provide pregnant women with so they can research this topic by consulting more credible sources and at a more critical level than merely “googling” it or relying on the advertising of the placenta business marketing and websites, in order to make an informed decision on whether or not to ingest their placenta (see below). Please take a look, and feel free to pass it along.

Update by Sarah: In my hundreds of interviews I have done with women on this topic, the need to honor the placenta definitely became clear to me. I buried my baby's placenta and it was a wonderful tribute with deep meaning to me. It is an inherent need in every culture and a missing piece in our modern one. The encapsulation does meet that need in a way, I have realized. I actually have another handout I made about a year ago that I give to all pregnant women that lists burial customs from every culture, and the meaning behind them. My patients LOVE that handout, and get excited about the idea of creating their own meaningful burial ceremony with their placenta. That has been a way I can keep the conversation positive and support them in meeting their need to honor their placenta, while offering an alternative to encapsulation. That felt like to much to cover for the scope of this article, so I appreciate the artwork holding that part in the discussion in the current blog.

Update by Sabine: Here is the link to Sarah's handout on "placenta burial rituals from around the world," which she shares with her pregnant clients and just updated for this blog. She has added a bit of information on early Chinese customs based on my research for my Master's Thesis decades ago on "Childbirth Customs in Early China" (University of Arizona, 1992).

And here is the link to a video Sarah has recently created that summarizes the latest research, which has links in it to all the research papers I reference in the video.

Both Sarah and I are concerned about the current popularity of placenta encapsulation and consumption as a postpartum tonic (In addition to the present blog, see also my previous one on classical Chinese medical attitudes toward human consumption of placenta "Placentophagy and Chinese Medicine." At the same time, we recognize, support, celebrate the desire of many new mothers, doulas, and midwives to honor the placenta as a sacred and powerful substance, rather than disposing of it as medical waste. So it is in the spirit of presenting a positive and constructive alternative that Sarah created this handout. I will also write another blog on early Chinese placenta rituals in the next couple of weeks. The suggestions in Sarah's handout are by no means intended as an authoritative statement on what YOU or anybody you know or work with should or should not do and are NOT the result of extensive scientific research. We simply want to provide a bit of inspiration to those of you who wonder what to do with your placentas or even how to think about them. We encourage you to let your imagination run free as you figure out whether and how to creatively express in your own ritual the sacred connection between baby, mother, family, community, and land that is by so many of us felt to be embodied in this substance, in the most meaningful and appropriate way for your cultural, social, religious, and personal beliefs and practices.In the meantime, I also buried my daughter's placenta and planted a tree on top, and here we are now...

Another update: Here are two brief articles: One from the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, published just last week, with a very strongly worded warning from the biomedical community:

"Placentophagy or placentophagia, the postpartum ingestion of the placenta-The evidence for positive effects of human placentophagy is anecdotal, and limited to self-reported surveys. Without any scientific evidence, individuals promoting placentophagy, especially in the form of placenta encapsulation, claim that it is associated with certain physical and psychosocial benefits. We found that there is NO scientific evidence of any clinical benefit of placentophagy among humans, and no placental nutrients and hormones are retained in sufficient amounts after placenta encapsulation to be potentially helpful to the mother, postpartum. In contrast to the belief of clinical benefits associated with placenta encapsulation, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently issued a warning owing to a case where a newborn infant developed recurrent neonatal group B Streptococcus sepsis after the mother ingested contaminated placenta capsules containing Streptococcus agalactiae. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended that the intake of placenta capsules should be avoided owing to inadequate eradication of infectious pathogens during the encapsulation process."

☝️Human placentophagy: a review

Alex Farr, MD, PhDcorrespondenceEmail the author MD, PhD Alex Farr, Frank A. Chervenak, MD, Laurence B. McCullough, PhD, Rebecca N. Baergen, MD, Amos Grünebaum, MD

Published Online: August 28, 2017

And one from Science Daily, published October 12.

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/10/171012091322.htm

Another update: An article by Daniela Blei, on “Project Placenta: A Little-Studied Organ Gets its Scientific Due

https://www.thecut.com/2019/08/what-is-the-human-placenta-project.html