Chinese Poetry and the Uses of AI

Note by Sabine: What follows below is an essay that Tom Ehrman kindly offered to write for this website. I first met Tom when he asked me for feedback on some medical translations at least many many years ago, but his attention has since shifted to translating poetry. Over the years, he has graciously shared his work in the “poetry corner” of my Imperial Tutor mentorship. He has also published a number of excellent articles in the Journal of Chinese Medicine (on bencao literature, classical acupuncture, “Taoist Tales from the Tang",” etc.), and I have always been much impressed by his care for elegant wording and cultural sensitivity. We got talking a couple of weeks ago about poetry and AI in the context of the Poetry Summer Sessions that I am currently teaching for my new students in the upcoming Foundations course and the members in my classical Chinese mentorship (Find out more about my classical Chinese offerings here). I personally have no interest in or experience with AI, so I am delighted that Tom offered to give us a glimpse here into his own use of this tool. To continue with this line of inquiry, Allen Tsaur will be joining me September 7 for a Tea Time Talk in my Imperial Tutor mentorship and has also requested to talk about this topic. I guess I’ll have to open my closed mind just a tiny bit and get out of my Luddite mindset. As I believe the following essay by Tom still shows, though, there is STILL no substitute for a human engaging their creativity and aesthetic sensitivities, especially when it comes to writing or translating poetry. So there….

A guest post by Tom Ehrman:

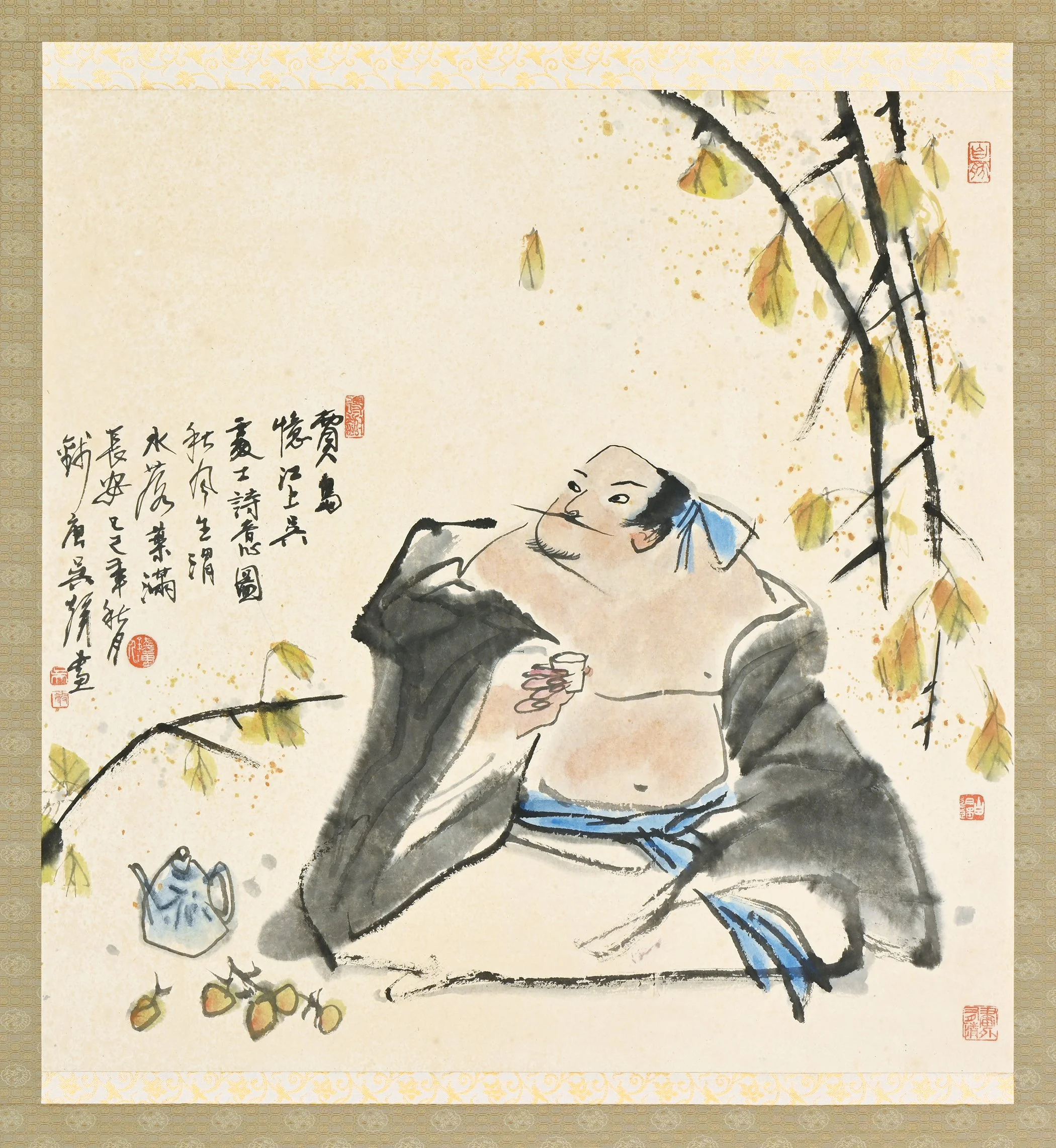

One unforeseen impact on the translation of Chinese poetry, that has literally occurred in the last year or two, is the advent of artificial intelligence (AI). Since AI is so new, I still have relatively little experience in using it, but what I have seen so far has impressed me greatly. It is, for me at least, a genuine help, not only in getting a rather vague, quick picture of what a poem means, though – be warned - its ability to translate is still far from perfect, but, more importantly, in explaining idioms (even ancient ones), historical associations, names of people, and geographical locations, with which many of these poems are filled. Gemini, the Google AI tool, is generally considered the best for research:

Even the most basic, free version can do a huge amount, and there is an option to do ‘deep research’ which will bring up a lot more, much of it related though not as specifically focused. It can search and interpret your own personal information

as well – a maximum of 10 files for the free version (by using the + button to upload, bottom left) – and can output information via the ‘canvas’ option in a format suitable for sharing, or copying and pasting to something like Word. I used both the ‘deep research’ and ‘canvas’ buttons to generate the outputs below, which I simply copied over to this article. The ‘image’ button is suitable for generating pictures (such as ‘draw me a picture of a flock of sheep’, which will generally give you a kind of Walt Disney-style cartoon – its artistic capabilities currently leave something to be desired).

You simply type in your question in the box where it says ‘Ask Gemini’.

So, Gemini is easy to use, and the following examples show how I applied it in a very specific way. I find that it is particularly powerful when answering these specific questions, into which it will often go in great detail, even more so if you ask it to do ‘deep research’. It can come up with information on even the most obscure topics, and, in the case of anything Chinese, must surely be mining Chinese-language data, as a lot of this would be difficult or impossible to find in English.

First example:

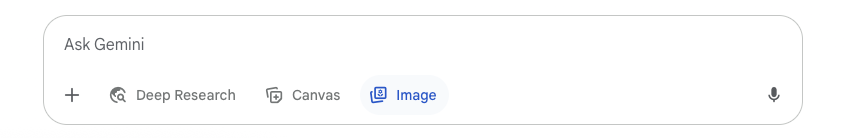

I have chosen two poems as examples, the first a poem by Jia Dao (779-843), a monk turned poet, about whom much has been written. Some of his poems, including this one, were translated and published by Mike O’Connor. Here it is, with my own translation below:

早秋寄題天竺靈隱寺

峰前峰後寺新秋,絕頂高窗見沃洲。

人在定中聞蟋蟀,鶴從棲處掛獼猴。

山鐘夜渡空江水,汀月寒生古石樓。

心憶懸帆身未遂,謝公此地昔年游。

“Written at Lingyin temple in Tianzhu in early autumn

Seen from the high window of a temple, nestled among the peaks, an autumnal view of Mt. Wozhou.

The calm of meditation pierced by chirping crickets, gibbons dangling where cranes nested before.

Night, and a bell chimes across empty water, cold moon rising above old stone tower on the shore.

The heart has raised its sail, but body’s yet to follow, to that place where Master Xie walked so long ago”

For me, there were two features of interest in this poem, about which I wanted to find out more. The first is 沃洲 (wòzhōu) in the first line, which generally refers to an oasis (as in Wenlin, for instance). Yet, Mike O’Connor refers in his translation to ‘a view of Mt. Wozhou’. Where is Mt. Wozhou, and which is the more plausible in this instance?

Question to Gemini:

“Here is a poem by Jia Dao – [full text given in Chinese]. Wenlin says that 沃洲(Wozhou) [in line 1] can mean ‘oasis’. Does it mean that here, or is Wozhou a mountain, or possibly a city, that might have been present in the Tang dynasty, visible from Lingyin temple in Tianzhu, 天竺靈隱寺 (from the title), and which Jia Dao might have known?”

Answer from Gemini:

“In Jia Dao’s poem “Early Autumn Inscribed (written) at Lingyin Temple in Tianzhu” 沃洲 (Wozhou) most likely refers to Wozhou Mountain. Here’s a detailed explanation:

- Geographical Plausibility: Wozhou Mountain is located in Xinchang County, Shaoxing City, Zhejiang Province. Lingyin Temple (天竺靈隱寺) is in Hangzhou, also in Zhejiang. Given their proximity within the same province, it is geographically plausible to see Wozhou Mountain from the “high window” of Lingyin Temple.

- Historical and Cultural Context: Wozhou Mountain was a very famous retreat and scenic spot in Chinese history, particularly from the Wei-Jin and Southern Dynasties through the Tang Dynasty. Many literati and poets left their footprints and poems there.

- Connection to Xie Lingyun: The last line of the poem, “Xie Gong (Duke Xie) once visited this place in past years,” directly links to Xie Lingyun. Xie Lingyun was a renowned landscape poet of the Southern Dynasties who famously lived in seclusion on Wozhou Mountain and composed many poems there. Jia Dao’s mention of “Xie Gong” in this context evokes the cultural imagery of Wozhou Mountain, expressing a remembrance of his predecessor and a longing for a reclusive life.

- The Imagery of “Wozhou”: While “Wozhou” literally means “fertile isle” and might suggest an “oasis” in classical Chinese poetry, when it appears as a proper noun, it typically refers to specific scenic mountains or waters. In this poem, combined with phrases like “among the peaks” and “high window”, it strongly emphasizes itscharacteristic as a mountainous landscape.

Therefore, Wozhou in this poem does not refer to a general “oasis” or a specific city, but rather to the historically renowned Wozhou Mountain. It carries rich cultural significance and a spirit of reclusion, perfectly complementing the setting of Lingyin Temple where the poet Jia Dao found himself.”

So Mike O’Connor was absolutely right, though, such is the concision of Chinese poetry that very often there can be different possible interpretations. Gemini’s answer to my first question has also answered my next question about this poem, which was about Master Xie (as I have him in my version, as opposed to “Duke Xie”), or Xie Lingyun, whom Gemini has discovered was a famous landscape poet from the past who actually lived in seclusion, at one point, on Mount Wozhou.

Second example:

The next poem I have chosen is by Ma Dai (799-869), a younger contemporary, friend and disciple of Jia Dao, who wrote in a rather similar style. Unlike Jia Dao, he is not well known, and, as far as I know, has never yet been translated into English. Here is a poem he sent to Jia Dao:

長安寓居寄贈賈島

歲暮見華髮,平生志半空。

孤雲不我棄,歸隱與誰同。

枉道紫宸謁,妨栽丹桂叢。

何如隨野鹿,棲止石岩中。

“Sent to Jia Dao while staying in Chang’an

These passing years I’ve seen my hair go grey, my lifelong ambitions turn to dust.

That lonely cloud at least will not abandon me. Together we can lead a solitary life.

A mistake to curry favour with the court and neglect to follow my heart’s true path.

How much wiser to follow the deer, and make my home among their rocky crags.”

In this instance, I was particularly interested in the imagery of the third line. What I have put – ‘A mistake to curry favour with the court and neglect to follow my heart’s true path’ – is actually a substitute for a line which talks about purple palaces and planting cassia/osmanthus bushes! What is going on? Given the tone of the rest of the poem, is this an expression of regret?

Question to Gemini:

“In this poem by Ma Dai – [full text given in Chinese] - please focus on the third line, its literal translation, and then an interpretation of its meaning. Is it an expression of regret?”

Answer from Gemini:

“This poem by Ma Dai, titled “Living in Chang’an, Sent to Jia Dao” (長安寓居寄贈賈島), is a poignant reflection on aging, unfulfilled ambition, and a longing for reclusion, addressed to his fellow poet Jia Dao.

Here’s a translation of the poem:

長安寓居寄贈賈島 Living in Chang’an, Sent to Jia Dao

歲暮見華髮, At year’s end, I see my grey hairs,

平生志半空。 Half of my life’s ambitions are empty.

孤雲不我棄, The solitary cloud does not abandon me,

歸隱與誰同。 With whom shall I return to seclusion?

枉道紫宸謁, In vain did I seek audience at the Purple Palace (imperial court),

妨栽丹桂叢。 Hindering the planting of cassia clusters (symbolizing success/official career).

何如隨野鹿, How much better to follow the wild deer,

棲止石岩中。 And dwell among the rocky cliffs.

Analysis:

- Lines 1-2: Aging and Unfulfilled Ambition

The poem opens with a somber reflection on the passage of time and the poet’s personal state. “At year’s end, I see my grey hairs” (歲暮見華髮) immediately establishes a sense of aging and the nearing conclusion of a period. This is directly linked to “Half of my life’s ambitions are empty” (平生志半空), indicating a profound disappointment with his career or life’s achievements. The “empty” (半空) suggests that while some aspirations might have been met, a significant portion remains unfulfilled, leading to a sense of regret or resignation.

- Lines 3-4: The Call of Reclusion and Solitude

“The solitary cloud does not abandon me” (孤雲不我棄) introduces a powerful image of nature’s constancy and companionship, contrasting with the fickle world of human affairs. The solitary cloud often symbolizes a free, unattached spirit or a hermit. This leads to the rhetorical question, “With whom shall I return to seclusion?” (歸隱與誰同). This line highlights a desire for retreat from the world, but also a yearning for companionship in that solitude, perhaps hinting at a shared understanding with Jia Dao, who himself was known for his reclusive tendencies and “bitter” poetic style.

- Lines 5-6: Disillusionment with Official Life

“In vain did I seek audience at the Purple Palace” (枉道紫宸謁) explicitly reveals the source of his unfulfilled ambition: a failed or unsatisfying pursuit of an official career. The “Purple Palace” (紫宸) refers to the imperial court, signifying the center of power and opportunity. His efforts were “in vain” (枉道). This pursuit “hindered the planting of cassia clusters” (妨栽丹桂叢). “Cassia” (丹桂) is a classical metaphor for a successful official career or high academic achievement. By pursuing court life, he neglected the more natural and perhaps more fulfilling path represented by planting these symbolic trees. This suggests a trade-off and a realization that the path chosen was detrimental to his true desires or well-being.

- Lines 7-8: Embracing Nature and True Freedom

The poem concludes with a clear statement of preference and a vision of an alternative life. “How much better to follow “the wild deer” (何如隨野鹿) expresses a strong desire to abandon the human world’s complexities and embrace the simplicity and freedom of nature. The wild deer symbolizes untamed nature and a life unburdened by societal expectations. The final line, “And dwell among the rocky cliffs” (棲止石岩中), solidifies this longing for a complete retreat, finding peace and shelter in the wilderness.

Connection to Jia Dao:

Ma Dai addresses this poem to Jia Dao for several reasons:

- Shared Sensibilities: Jia Dao was famous for his “bitter” (苦吟) and often melancholic poetry, frequently depicting desolate landscapes and the struggles of a marginalized scholar. He himself experienced difficulties in his official career and often expressed a desire for reclusion. Ma Dai likely saw a kindred spirit in Jia Dao, someone who would understand and resonate with his feelings of disillusionment and longing for retreat.

- Mutual Support: Poets often exchanged verses as a form of communication, commiseration, and mutual encouragement. By sending this poem, Ma Dai was sharing his inner turmoil and seeking empathy from a friend who could truly grasp his sentiments.

- Common Themes: Both poets often explored themes of nature, solitude, the frustrations of official life, and the passage of time.

In summary, Ma Dai’s poem is a heartfelt lament from a Tang Dynasty scholar who, at the twilight of his active life, reflects on his unfulfilled aspirations in the official world and expresses a profound yearning to abandon it all for the peace and freedom of nature, a sentiment he knew his friend Jia Dao would intimately understand.”

Readers will notice that Gemini has made a fairly decent attempt at a translation in this instance, which is more literal than my own. Though one should be cautious about its translation abilities, particularly for Tang dynasty poetry, as I mentioned above, it is still often useful for an initial quick idea of what the poem is probably about. One can then refine one’s understanding by asking specific questions about anything one finds puzzling, as I have done here. It is interesting, incidentally, that Gemini mentions the 苦吟 (bitter intoning/reciting) of Jia Dao above, as this features strongly in a recent book about ‘poet-monks’ by the expert on mediaeval Chinese poetry, Tom Mazanec.

Then it is up to you as to how you wish to interpret the poem, and how you think a literal translation might be improved, without losing the overall meaning of the poem. For me, translating poetry is not like translating Chinese medicine, for instance, where it is important to be fairly literal for the sake of accuracy. One is aiming for something that is readable and captures the spirit of the poem, while at the same time staying as faithful as possible to the original. The reason I changed the third line is that I felt an expression that people nowadays could understand without any difficulty was, in this instance, more ‘faithful’ to the original in its own way, and better than a confusing line about ‘purple palaces’ and ‘cassia/osmanthus’, which, though beautiful, would sound strange, and then require a lengthy footnote to explain!

If this essay by Tom Ehrman has made you curious about reading literary Chinese sources yourself in the original, please check out my various offerings on classical Chinese at my website www.translatingChinesemedicine.com and consider joining the new cohort for my 2-year Triple Crown intensive training program. We start on September 11 with the Foundations course, and the sooner you apply, the sooner you can join us for poetry readings and written and recorded lessons in the meantime.