Why I translate the Chinese medicine classics

Somebody asked me recently why I do what I do in my professional capacity as a translator of classical Chinese medical literature and teacher in the art of reading the Chinese medicine-related classics. It is always a good idea to question the direction of my life and the way I spend my precious remaining time in this body on this earth, especially in the very short summer season on Whidbey Island, when I could just be snoozing in the sun, picking thimbleberries, or frolicking in the waves. So here is my honest effort at an answer, which is basically part genetics and family history, part dumb luck, and part life calling:

I come from a long line of medical doctors in my family in Germany, including both of my parents, my sister and her family, two grandparents, and many other relatives. So I grew up helping out in father’s hospital and spending a lot of time around adults who were physicians and very much committed to their healing work as the most noble profession they could imagine. I was a rebel and wanted nothing to do with my family tradition. When I was 18, after one semester of East Asian Studies at the university in Germany, I left my native Bavaria and moved to Taiwan where I studied classical and modern Chinese, but unfortunately not medicine. I had the most wonderful time being immersed in Chinese culture, both modern and ancient, learning to read classical poetry, visiting the Palace Museum regularly, studying calligraphy, Erhu, and Qigong, learning to cook Chinese food, and living with my Chinese roommates. I never wanted to leave, but after two years, my parents convinced me to return to Germany to finish my undergraduate degree. Then I got a scholarship and moved to the US to continue my graduate studies, again in East Asian Studies.

It took over ten years for me to discover my academic interest in medicine, when I incorporated courses on ethnomedicine and medical anthropology as part of my doctoral program at the University of Arizona in Tucson, and then chose the gynecological section in Sun Simiao’s Beiji qianjin yaofang as my dissertation topic. Before then, my research focus had been on early Chinese literature, religion, philosophy, and natural science. It was partly the experience of giving birth to my own daughter and witnessing the dysfunctional US culture around hospital births and obstetrical, postpartum, and neonatal medical interventions, that made me realize the potential of the human body, and of childbirth and reproduction in particular, as an angle for studying culture. I happened to have a medical anthropology professor, Mark Nichter, who was very excited about my ability to read the ancient texts and kept asking me the most wonderful questions, so I just had to keep digging for answers. A quest that continues to this day…

After graduation, I was delighted to discover that my knowledge of traditional Chinese medicine and my ability to read the literature and dig for answers to medical questions was useful not just for teaching in regular academia. More and more, my professional work in researching, writing, translating, and teaching shifted towards serving an audience of Chinese medicine students and practitioners because they cared about my knowledge in a far more direct way than a traditional academic audience.

In regard to choosing translation specifically, I have always been attracted to the classics of any tradition and had a fascination with ancient texts and languages, starting with my studies of Classical Greek and Latin in High School. I was delighted when I got to explore the Warring States classics in my East Asian Studies program in college and have always soaked up the wisdom in these ancient Chinese texts. I also love language and writing in general, so working as a translator feels like the perfect fit. I consider myself very lucky to have found a field of academic work where I have literally thousands of practitioners appreciating my translations because they are able to directly apply them in their clinical practice, making a real difference in alleviating the suffering of their patients.

As I mentioned above, I greatly enjoy reading the classical medical texts, as well as the challenge of translating them. I am also keenly aware that my clinical colleagues in the West for the most part are unable to access the precious content of these texts and are therefore greatly appreciative of any translations I produce. It is simply very rewarding when I translate a selection of formulas or a passage from the Huangdi Neijing, share it with the members in my mentorship, in my courses, or in a blog post on my website, and receive many grateful responses from practitioners. I am firmly convinced, and become more certain with every text I translate and every course I teach, that there is such a wealth of insight and knowledge and experience in these classical texts that can benefit modern practitioners of Chinese medicine in the West, and ultimately even an audience beyond the Chinese medicine practitioners!

I started teaching translation courses as part of my teaching load at the College of Classical Chinese Medicine, at the National University of Natural Medicine in Portland, Oregon. Prior to that, I had mentored individual students and small groups with widely varying backgrounds privately. Eventually, I became the head of the “classical texts” committee that became the core of the doctoral program there, and spent years exploring with fellow clinical faculty and students how and why and to what extent it made sense and was possible to teach students of Chinese medicine to read the medical classics in the source language in a three-year series of intensive classes. I was always crystal clear with my colleagues and students, however, that it is impossible to teach a Western student with no background in Chinese to independently translate or even read the ancient classics on their own (unless they are straightforward formularies) while engaged in a full-time clinical program, and that it is essential to lean on secondary sources and experienced teachers for support. After leaving that position, I created a whole new online program, through which I now teach classical Chinese to medical practitioners in three levels over two years.

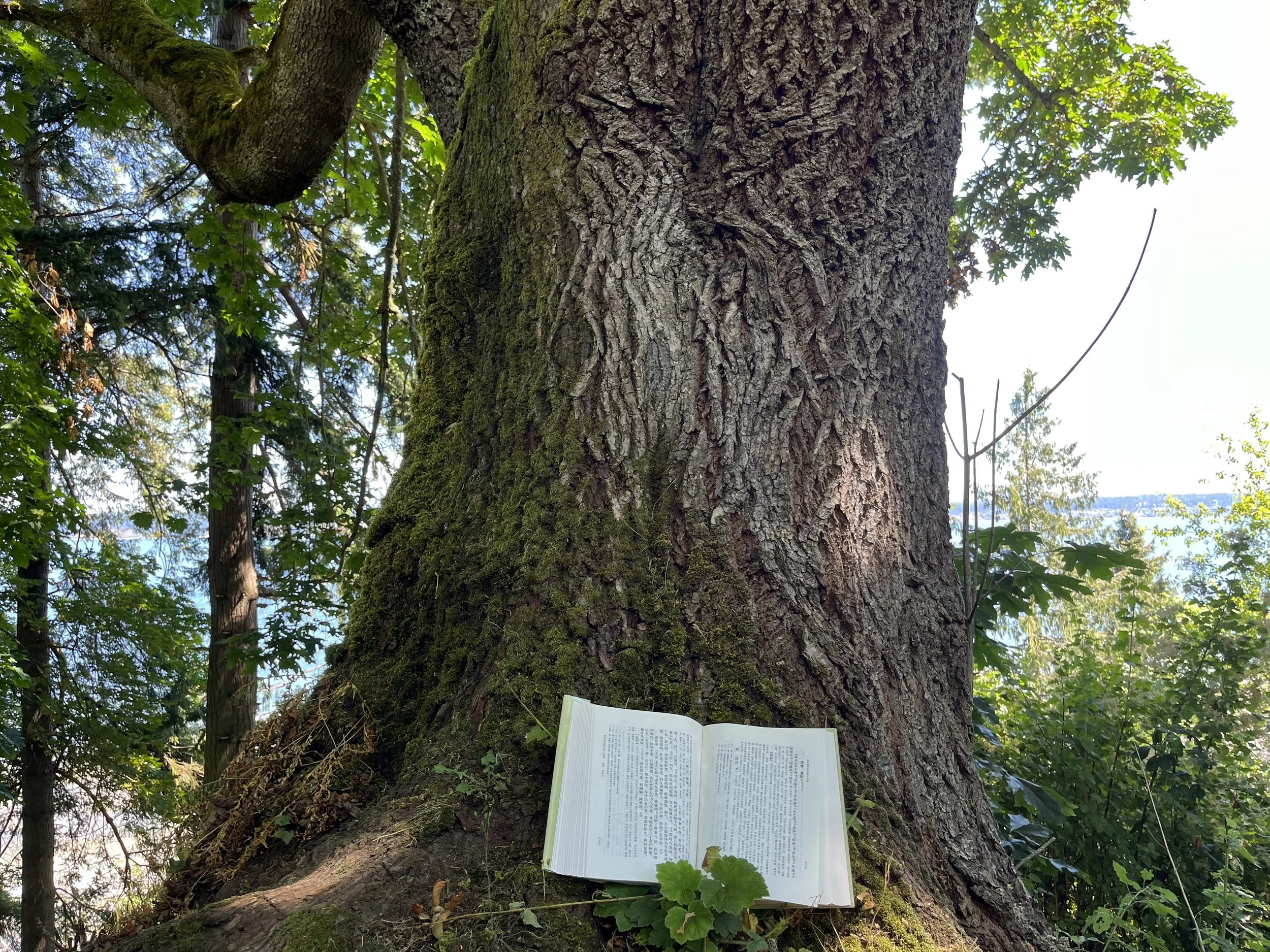

My motivation is two-fold: First, being able to read a source text directly, even with limited linguistic proficiency, will always be far far superior than to just read a translation, no matter how good that translation may be. I love reading the classics with my students and guiding them along. The process alone is its own reward. As such, there is a huge benefit to teaching students to read the classics in the source text alongside existing Western-language translations, possibly supported by modern Chinese versions and historical commentaries. Second, producing published translations of the medical classics is hugely time-consuming and financially unsustainable without outside funding. There are so many texts that need to be made accessible to practitioners in the West who are waiting for this material. I am one person with limited time and resources, and there are not that many other skilled translators out there dedicated enough to produce high-quality work. So I am hoping, over many years and decades, to slowly build a collaborative structure of international students and colleagues, including practitioners and scholars both in East Asia and elsewhere, to accelerate the process of producing high-quality translations of these important texts by combining our various skills. I currently direct a mentorship on “Reading the Chinese Medicine Classics” where we meet up for monthly “text readings” on Zoom to read and discuss a variety of classical texts. These meetings include colleagues and students from America, Canada, Europe, UK, and East Asia. The insights we gain from these gatherings are quite deep and hopefully will result in collaborative publications at some point. For now, it is enough that we gather once a month to read texts, contemplate their clinical relevance, and explore the linguistic and other challenges in collaboration. How lucky we are that technology provides the tool for such a gathering! My two-year “Triple Crown” Intensive, which starts with a new cohort every two years, including this September 11, 2025, creates a small but steady trickle of new translators to feed into this growing stream of properly trained future translators of medical texts. At some point, I will get to sit under my beloved maple tree with my goats, watch the sun go down over the sea, and know that others continue the work that my colleagues and I have started….