Do I get to eat it?

This short essay was inspired by an interesting coincidence in timing two weeks ago (and apologies that I didn’t get it finalized and posted until now). Credit for inspiration, art, and all the beautiful pictures goes to Hue Hoang.

On the one hand, we have the federal government in the US, which, with intentional cruelty, was stopping food assistance as part of the shutdown that just ended in the middle of my drafting this essay. On the other hand, I happened to discuss the following passage from Confucius’ Analects 《論語》 in my classical Chinese class:

“Duke Jing of Qi questioned Confucius about government.

Confucius answered: “Have lords be [true] lords and servants be [true] servants, have fathers be [true] fathers and children be [true] children!”

Duke Jing said: “What a great answer! Indeed, if lords were not [true] lords and servants not [true] servants, if father were not [true] fathers and children not [true] children, though there may be grain, would I get to eat it?”

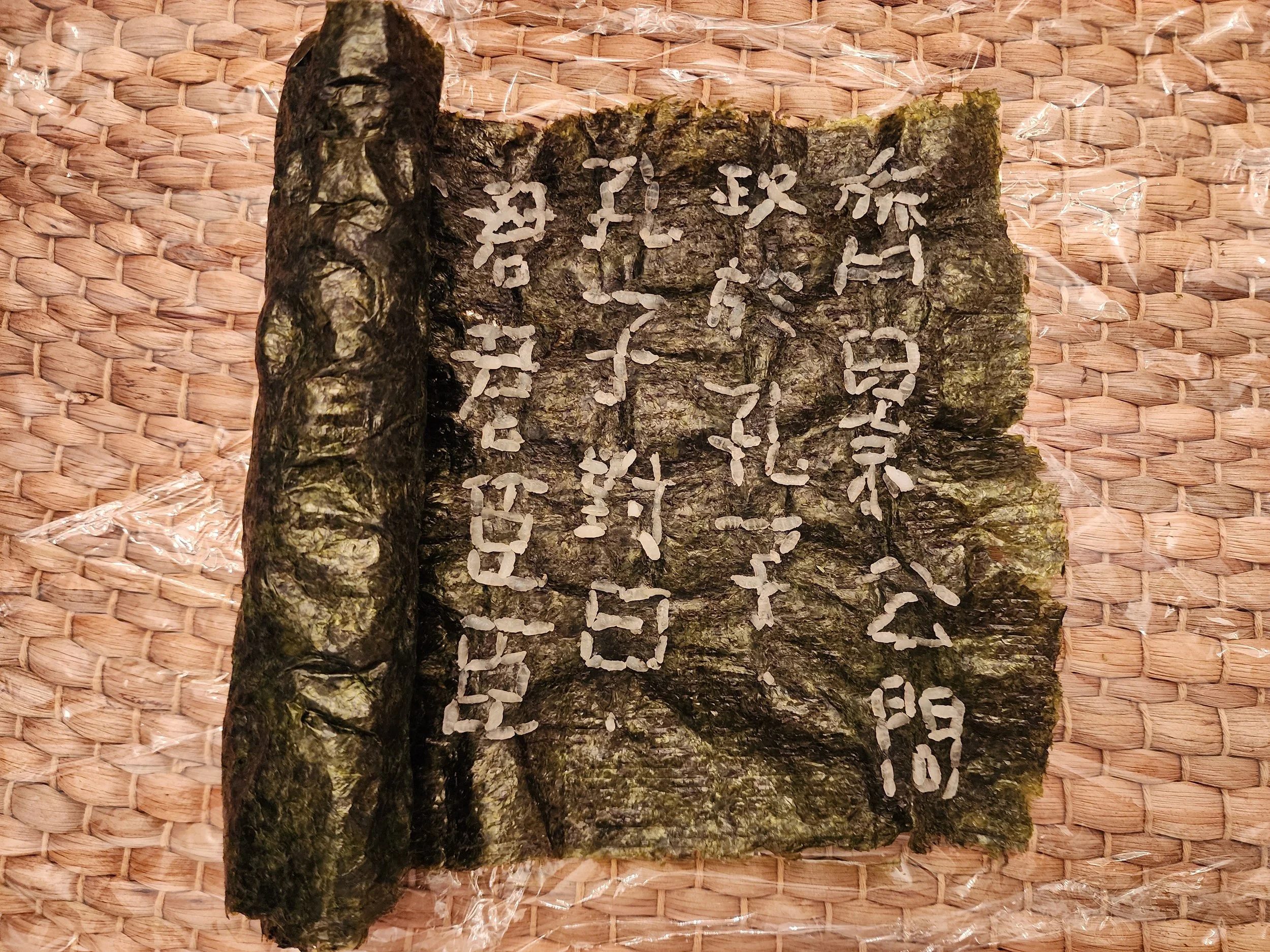

齊景公問政於孔子。

孔子對曰:「君君,臣臣,父父,子子。」

公曰:「善哉!信如君不君,臣不臣,父不父,子不子,雖有粟,吾得而食諸?」

As I always do, I encourage my students to engage with the material not just on an intellectual level, but from the heart. What is Confucius’ point here, and what is the nuanced meaning in the Duke’s laconic answer of 善, which can mean either simply “good” or “great,” simply expressing a general sense of agreement, or something more specific like “skilled.” Could it be ironic, as in “Well, that sounds grand in theory, but what the heck am I, as the ruler of my state, supposed to do with that in concrete terms?” I happen to be on a mission these days to explore the teachings of Confucius, to perhaps learn a bit about cultivating virtue at a time when it feels like I personally, this country, and the world are all in dire need of that. And to me, the longer I read Confucius’ supposed own words through the Analects, the more I see them as very different from, and even opposite to, the government-sponsored system of hierarchical oppression called “Confucianism” that has been imposed on hundreds of generations of Chinese kids, servants, women, and other people at the lower end of the traditional Chinese social structure and continues to be perpetuated even today in traditional Asian family and educational settings. We are so used to reading Confucius through the lens of Confucianism that it is easy to lose sight of the original meaning.

The quote above is the classical expression of Confucius’ project of “rectification of names” zheng ming 正名, i..e ensuring that designations correctly match reality. This refers to his passionate belief that if only each of us were to truly and sincerely, to the best of our ability, fulfill our “names,” in the sense of the social roles that we find ourselves in, in accordance with the high standards expressed in the classical texts from the Golden Age of the early Zhou era, society would return to the peace, harmony, caring, and justice that had marked that ancient past. To truly understand the significance of this “rectification of names,” it is helpful to know that the character 名, which means “name,” “title,” or “designation” and is usually pronounced in the second tone, has an alternate pronunciation and slightly different meaning: It can also be pronounced in the fourth tone and is then used interchangeably with its homophone 命, meaning “mandate” or “order,” or even “destiny.” In other words, we are not just talking about job titles here like “supervisor” or “manager” but about socially constructed identities, our calling in life, what my friend Lillian Bridges always referred to as our “Golden Path.” For most readers of my books and this blog, this vision by Confucius invites you to consider what it means for you personally to be a true healer, to embody this role in every word, thought, and action, far beyond a white coat, letter behind your name, or herb bottles and needles on your shelf. This reminds me of Wang Fengyi’s simple but powerful advice not to judge or blame others but to look in the mirror and focus on yourself and what you can do, in your little corner of the universe.

One of the most important insights I have had recently is that Confucius did NOT aim his teachings at the people on the lower end of the hierarchical relationships in traditional China but always addressed the people in power: the men, the nobles, the husbands and fathers and rulers! In my mind, this fundamentally alters the tone of his message. He is not calling on us to be blindly subservient to our superiors, but to be loving, kind, considerate, just, selfless, and responsible towards those inferior to us. And this is how we have to read the quote above! Quite the courageous act when you look at it from this angle, isn’t it, to tell the ruler that if there is disorder in his realm, it is because he is not fulfilling his role and is not worthy of being called by that name…

Don’t you wish our current politicians would drop their bickering and blaming and perhaps all gather around a certain big oval desk and read a copy of the Analects out loud to each other and then figure out together what it means to be and act as junzi 君子, “cultivated people” or “lords”? Let the president be “presidential,” let the senators be “senatorial,” and let the representatives truly represent the people who elected them? What would Confucius do if he were alive in America in this moment? What would he have to say about the construction of a gold and marble ballroom in the midst of food stamps being cut? Then again, contrary to what the story above suggests, Confucius was never able to find stable employment and a truly receptive ear for his teachings among the rulers in his lifetime, so maybe things really haven’t changed that much in the past 2.5 millennia.

But don’t let me end on a pessimistic note! Instead, the whole intention with this blog is to bring you joy and hope and inspiration by sharing a beautiful thing that happened in my little word: One of my classical Chinese students, Hue Huang, took it upon herself, in an act of pure Confucian dedication to studying and virtuous self-cultivation, to transcribe the above-mentioned passage in a medium called “rice calligraphy.” As she told me herself, it took her five “grueling” hours, after which she consumed (or literally “internalized”) the whole art piece as an evening snack while contemplating the preciousness of grain, impermanence of her work, and changeability of text and context!

Here is Hue’s list of ingredients, in case you are now tempted to replicate it:

• Nori seaweed,

• cooked rice (which dried out by the end of the 5 hours lol),

• skewers to place the rice and moistened with tea to help lubricate the skewer so rice doesn’t stick on the skewer, but sticks to the nori.

• Decor was cucumbers, (seasoned) egg (fried as a thin omelet and sliced), and kabocha pumpkin for the seats.

I have two left hands when it comes to things like this, so don’t wait for me to share my own example of “rice calligraphy.” But if this post has inspired you to give it a try, please let the rest of us know in a comment below, and send me a photo if you want me to share it here….