On Caution in Medicine

Advice from the 18th Century, translated by Tom Ehrman

What follows is a guest blog written and translated by Tom Ehrman. Please note that the following introduction and two excerpts come from a longer article that will be published in the forthcoming issue of the Journal of Chinese Medicine. It is my hope that this little taster whets your appetite and perhaps inspires you to support the Journal by becoming a paying subscriber. I am grateful to both Tom and to Danny Maxwell for their tireless work and for giving me permission to share this excerpt here.

Written in 1767, four years before his death, Shènjí Chúyán (Humble Advice on Caution in Treating Illness) is the final medical work of the famous Qing dynasty physician Xu Dachun (1693-1771). Though much of the material in this short book of essays is of limited interest to modern practitioners, his thoughts on subjects such as tonics and medication, childbirth and the care of infants, the elderly, weights and measures, choosing a doctor, esoteric remedies and the medical literature are as relevant now as they ever were, and these are now translated for the first time and presented below.

Xu Dachun was one the foremost physicians of his time to advocate a return to the medical ideas of antiquity, in particular the Nèijīng (Inner Classic) and the works of Zhang Zhongjing. He was also well known for his polemical style of writing and his criticisms of contemporary practitioners, and this book demonstrates that he had lost none of his ferocity and caustic wit in old age! One particular target of his anger was the overuse of ‘warming tonics’, the growth of which he attributed to Zhao Yangkui and Zhang Jingyue of the late Ming dynasty, who developed the school of ‘warm supplementation’ (wēnbǔ) which had become increasingly popular during the first half of the Qing dynasty. Though his constant warnings about the fatal dangers of the indiscriminate use of such tonics are almost certainly an exaggeration, designed to shock his readers into changing their ways, his words of caution are still useful even now.

Readers nowadays may also find much else that resonates, and his thinking should appeal to practitioners of classical Chinese medicine (CCM) and Jingfang in particular. Other physicians, such as Chen Xiuyuan (1753-1823) a little later, took his ideas further, and this movement – known as Hànxué (Han learning) - gained rapid momentum, with a proliferation of commentaries on the ancient medical classics being written during the 19th century, and going on to form the bedrock of most modern forms of Chinese medicine.

The text is anecdotal in style, easy to read, and requires little explanation, being largely free of much of the more technical language of Chinese medicine.

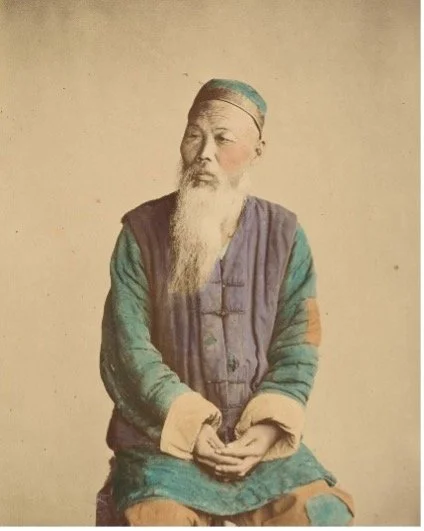

On Elderly People

Elderly couple, hand coloured photos from the late Qing dynasty, 1870-80, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC.

“In order to live a long life, yin and yang must be in balance. If there is too much yang, one must supplement yin; if there is too much yin, one must supplement yang. Those with too much yin, however, only number one or two out of ten, whereas those with too much yang number eight or nine out of ten. Furthermore, if yang is excessive, one should not only supplement yin, but should also clear fire to protect yin. Thus, the elderly often experience heat in the head, loss of hearing, a flushed face, and dry stool, all of which are manifestations of various yang symptoms.

Doctors who give prescriptions to elderly people, regardless of whether they are ill or not, always supplement yang as their priority. However, an excess of heat can generate wind, which invariably gives rise to conditions such as a stroke. This is an invitation to ill health. If, by chance, there is any external wind, cold, phlegm or dampness, these evils must be swiftly expelled because the qi and blood of elderly people do not flow smoothly. How could they bear these evils to be trapped, causing further difficulties for their qi and blood? Therefore, when treating an elderly person who has contracted an external illness, the approach should generally be the same as for a strong young person. However, if one truly observes a condition of deficiency and weakness, then light, bland remedies should be used, to provide a measure of support for the upright.

If the person is without illness, then, to regulate health, one should ascertain the imbalance of yin and yang, and increase or decrease accordingly to restore balance. A thousand year old tree will often self-combust; once its yin is exhausted, fire will blaze. This is true for all living things. When treating an elderly person [whose yin is depleted], one must absolutely not use pungent, hot medicines. Such herbs further exhaust their yin qi, and assist hyperactive yang, causing a flushed face, bloodshot eyes, blocked qi, congested phlegm, a surging pulse, and dry skin. At a venerable age, this is tantamount to the misery of being consumed by fire.”

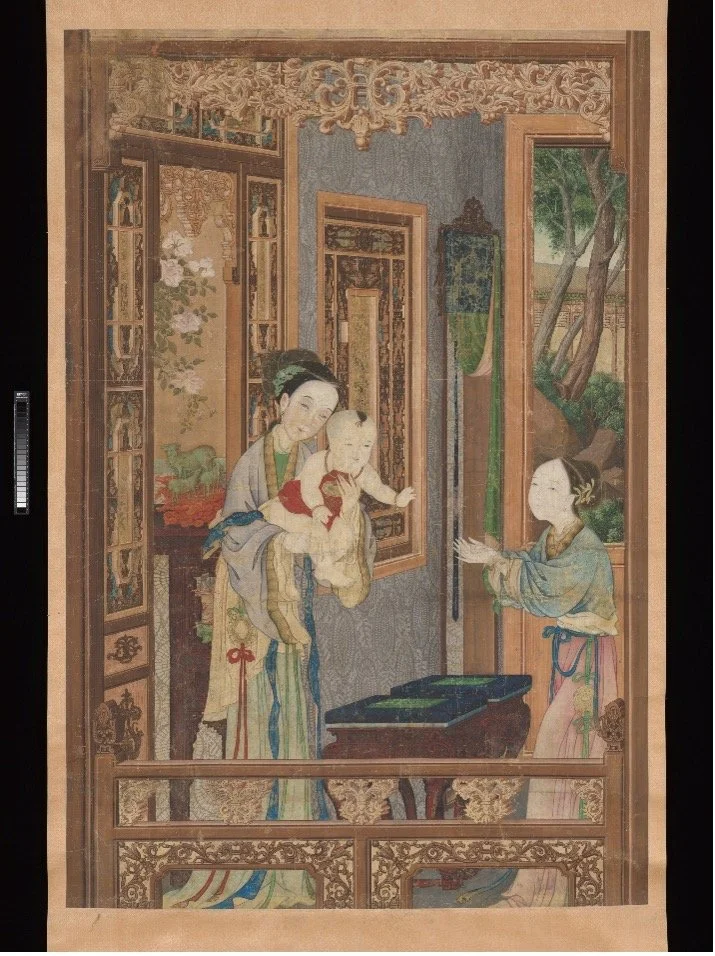

2. On Infants

Woman, child and nurse, Anonymous, 18th c., Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC

“The illnesses of an infant are nothing more than two things: heat and phlegm. Their essential being is pure yang. If they are held in people’s arms all day long, bundled in warm clothing, and swaddled in blankets, this creates heat both internally and externally. Heat generates wind, the wind and fire fanning each other. If the child is then suckled without pause, phlegm is bound to be generated. When phlegm is condensed by fire, it becomes as tough and sticky as glue. If feeding continues without interruption, new and old phlegm accumulate daily, leading to bloating and wailing. People then force-feed more milk to stop the crying. This causes the chest to become congested, the breathing to become blocked, the eyes to stare, and the hands to twitch. They diagnose this as ‘fright wind’ (infantile convulsions), but, in reality, it’s not a seizure; it’s simply that the child is bloated to the point of death!

If, at this point, you tell the parents to reduce the child’s clothing and stop feeding them, they become furious. They will argue that the child is already so weak - how could you possibly let them be cold and hungry as well? They will curse you. Doctors who do not understand what is going on will either use harsh, drying medicines, or try to “tonify” the child with Shēn (ginseng). By the time the phlegm is hardened and the qi congealed, the child is beyond saving. I have seen countless such cases. I advised the parents to regulate the child’s temperature, stop giving them milk, and nourish their stomach with a thin rice broth, while gently administering herbs that disperse phlegm and regulate qi. Among those who listened, eight or nine out of ten children were cured. For those who didn’t understand this principle and instead thought my words were crazy, not a single child survived.”